A Celestial Discovery

Imagine a bitter Tuscan night in the winter of 1610. A certain man directs his rudimentary telescope to the heavens. As he focuses his attention to Jupiter, he sees something astounding which brings him much joy. Moons circle the great Giant. A tale of incredible scientific discovery follows. Likewise, this discovery also leads to stories of how forgers live in a fantasy world of unreachable riches. The story of Galileo’s Sidereus Nuncius gives unique insight into the world of forgery.

In the book Sidereus Nuncius, Galileo reported on his discovery of moons orbiting Jupiter. That proof rests at the heart of geocentric (Earth centered) versus heliocentric (sun centered) theories of the universe first formally posited by Copernicus. Consequently, through the discovery of Jupiter’s moons, Galileo moved ever closer to confirming Copernicus’ theory.

A History of Forgery

A 2013 article published in the New Yorker Magazine told the complex and convoluted story of an edition of the Sidereus Nuncius “written” by Galileo Galilei. Imagine today’s financial value for such a work. The article by Nichola Schmidle is worthy of a novel. It features unscrupulous book sellers, proofs of forgery, disclaimers, and lawsuits.

The intriguing process of proving the authenticity of any book of any age winds through the New Yorker article. The story begins in June of 2005 when a book seller from New York engaged in the purchase of a Sidereus. Nick Wilding, a Renaissance historian at Georgia State became involved. Horst Bredekamp, a Berlin expert in assessing art created by important people in Europe’s historic intellectual community, also plays a role. Other experts from across the globe joined in the search for authenticity. Revelations of forgeries, along with withheld authentication articles and further intrigue, followed. In 2013, Martino Massimo De Caro, of circuitous involvement and questionable accreditations, was found guilty of embezzlement.

Overall, the article shows how forgers use various methodologies to recreate “aged paper, inks and printing press impressions”. The skill with which this is achieved has risen to new heights. Therefore, the world of antiquarian collectors, analysts, scientists, and passionate researchers must take a cautious approach to any new discovery. The human imagination has proven itself guilty of forgeries over the centuries, no less the Sidereus.

Star Gazing and the Sidereus Nuncius

Let us, however, focus on the Sidereus Nuncius.

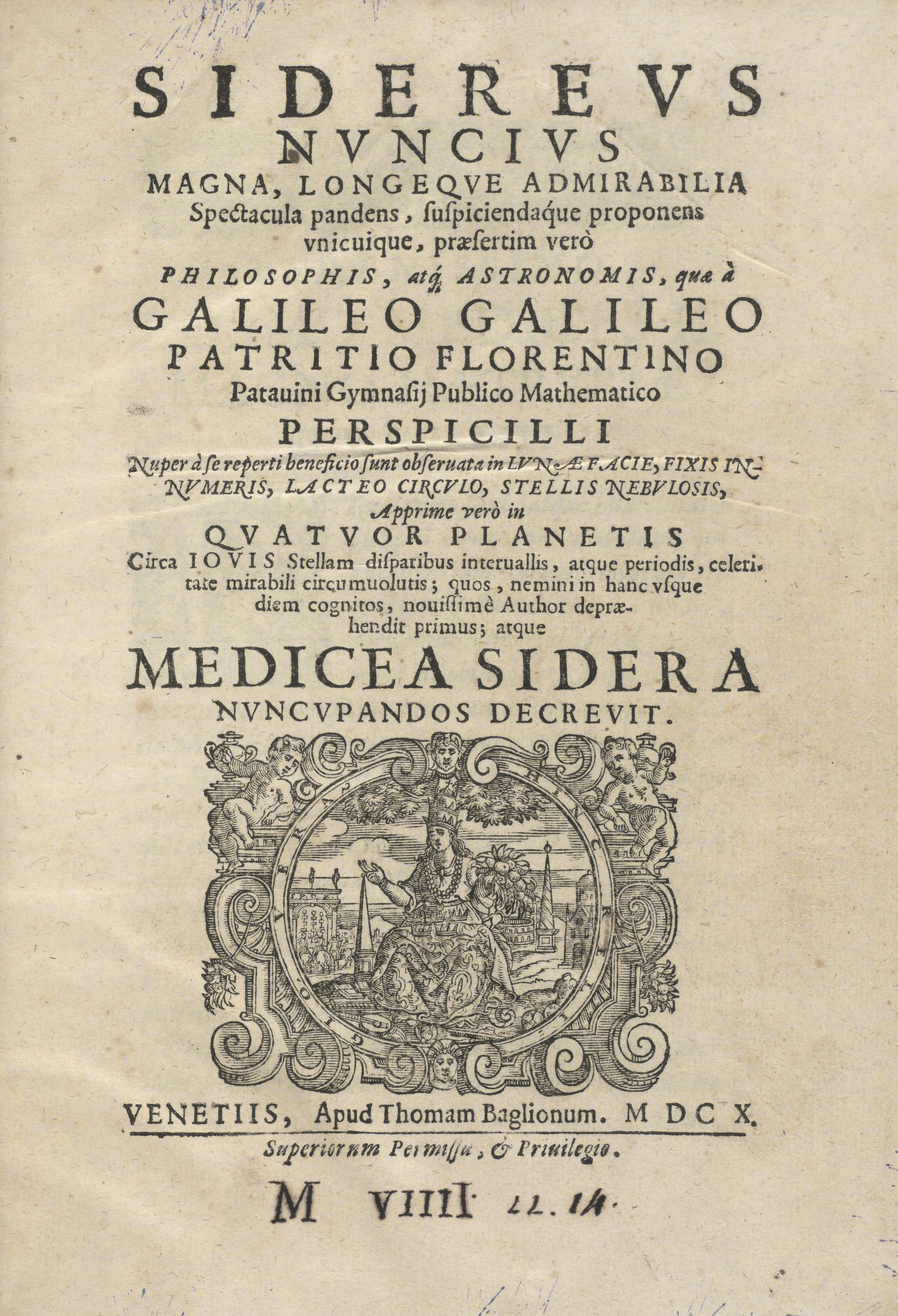

The lengthy title of this work is, “The Starry Messenger (sic), Revealing great, unusual, and remarkable spectacles, opening these to the consideration of every man, and especially of philosophers and astronomers; as observed by Galileo Galilei, Gentleman of Florence, Professor of Mathematics in the University of Padua, with the aid of a spyglass, lately invented by him, In the surface of the Moon, in innumerable Fixed Stars, in Nebulae, and above all in four planets swiftly revolving about Jupiter at differing distances and periods, and known to no one before the author recently perceived them and decided that they should be named The Medicean Stars.”

Hans Lippershey, a Dutchman, figures in Galileo’s studies. Some suggest Hans, actually invented the telescope. Records show his attempt to file a patent for an early design. However, Galileo learned of this device and improved the power of his telescope from between 8x (x meaning ‘power’) and 10x to 20x, by polishing his own lenses. Keep in mind, Europe, in this period, had fervent and frequent exchange of artistic inspirations and scientific findings. Thus, the world seemed ready for these developments. Certainly, geniuses like Lippershey and Galileo stood all too ready to oblige.

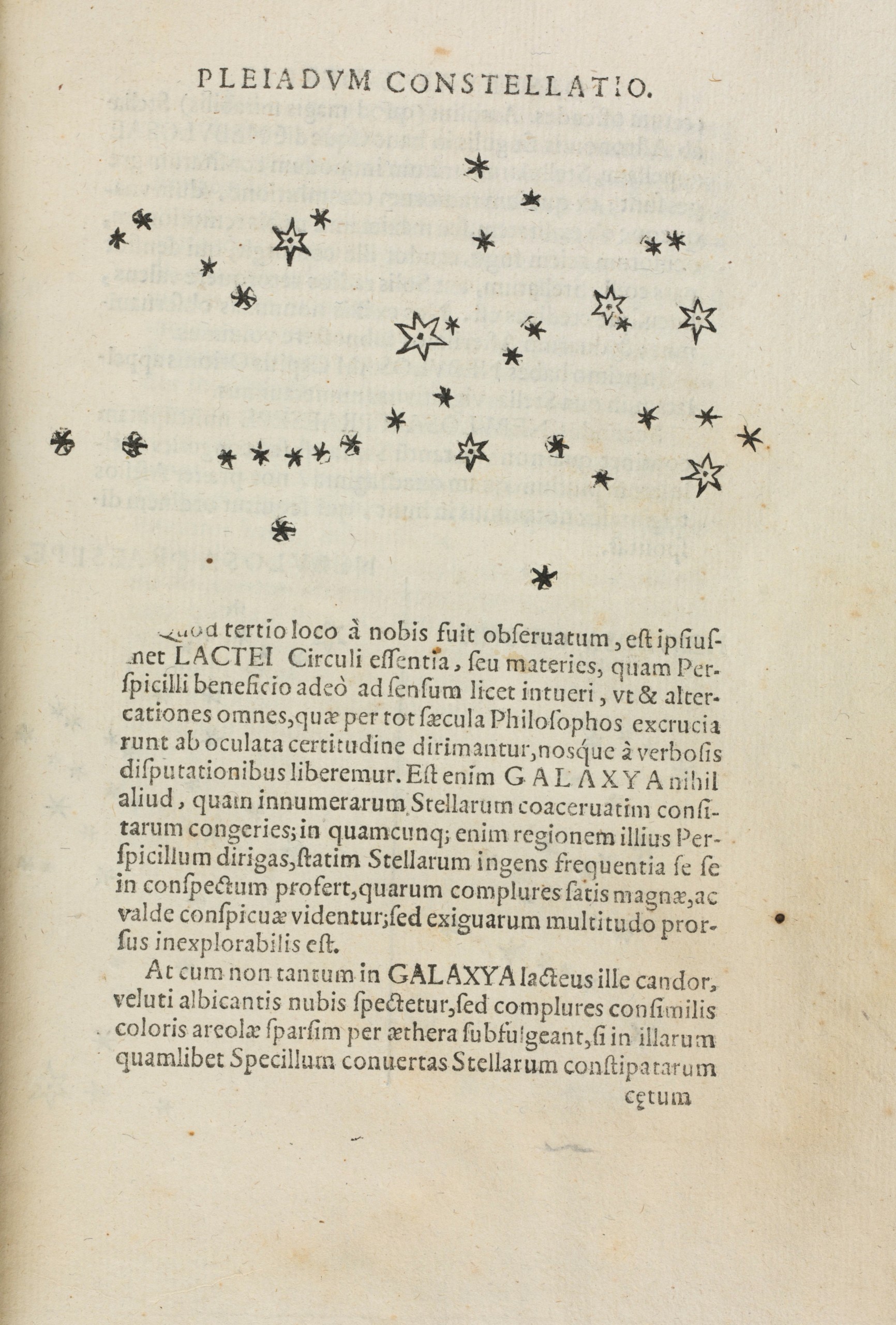

Of the 550 editions of this work printed in Venice, 150 are known to survive. The books measure 10″ tall by 7.5″ inches wide. Although only 60 pages long, the Sidereus Nuncius (Starry Message in Latin) contains drawings of the constellations of Orion, Pleiades, Taurus and others, as well as copper etchings of the moon.

Galileo’s Enduring Legacy

Consider the year in which the Sidereus was published. Despite limitations, Galileo calculated the size of the crater mountains on the moon as up to four miles high. It astounds me to think calculations of that magnitude, across almost 239,000 miles of space between his observatory and the surface of the moon were even possible. Imagine.

When next in Florence, I hope you will take time to visit the Galileo Museum. There you will find an original, authenticated copy of the Sidereus. The museum stands next to the Uffizi, a too frequently overlooked invaluable treasure of the city and of scientific history.