Layered History in Scrovengni Chapel

When Giotto di Bondone began his work inside the Arena Chapel, he had a great deal more than fresco design on his mind — ruthless money lenders. The commission came to Giotto from the Scrovegni family, and the chapel equally bears the names Scrovegni Chapel and Arena Chapel.

Why “Arena”? The chapel was built in the general area of the Roman amphitheater of the Padua colony. The city rose along the banks of the Medoacus Major, today called the Brenta River. The colony thrived for centuries. The structure was part of a once huge palace which the Scrovegni family built after buying the land in 1300.

A Sinner’s Penance

Enrico Scrovegni, ruthless son of the rich Reginaldo — whom Dante Alighieri had consigned to hell as a usurer — made his living as did his father: by lending money at interest. During the Middle Ages, society frowned upon this type of business. However, by the beginning of the 15th century, such business transactions were tolerated. Some theorize perhaps Enrico commissioned the chapel frescoes as a means of expiation for the ‘sin’ of usury. As the Italians say: qui lo sa, who knows? However, this theory has some support because the chapel was dedicated to the Madonna della Carità, the Madonna of Charity. Inside the front entrance rests a fresco depicting Enrico genuflecting and donating the chapel, so as to earn forgiveness from Christ.

Complexity of Fresco Painting

As some of you may know, the time required to paint frescos depends on what is called a giornata. This refers to the amount of work that can be done on the prepared surface in one day. Experts calculate Giotto and his team took 625 days to complete the entire interior surface of the chapel.

Frescoists used a cartone, a large sheet of paper, to draw the day’s giornata. The artist placed the completed drawing against the wet surface of the wall or ceiling. Then, with a very sharp needle-like tool, the artist poked holes through the lines of his drawing. Workers placed wet sinope — reddish brown ground hematite from Turkey — in a thin cotton bag. The artist outlined the holes using the sinope so the reddish color of the ground mineral adhered to the wall. After removing the cartone, the outlines of the drawing remained. These dots guided the artist as they created the images. Overall, the creation of a fresco involves a staggering amount of work.

Giotto’s Work in Scrovegni Chapel

By 1304, Giotto, who was between the age of 36 and 38, had begun work on the fresco cycle. Along with an estimated forty collaborators, he presented scenes that focus on the life of the Virgin Mary and celebrate her role in human salvation. Giotto had likely completed or nearly finished his work by 1305, based on the date of consecration for the chapel. Giotto’s years in Padua are well documented, and the works in the chapel are the only artwork firmly attributable to him.

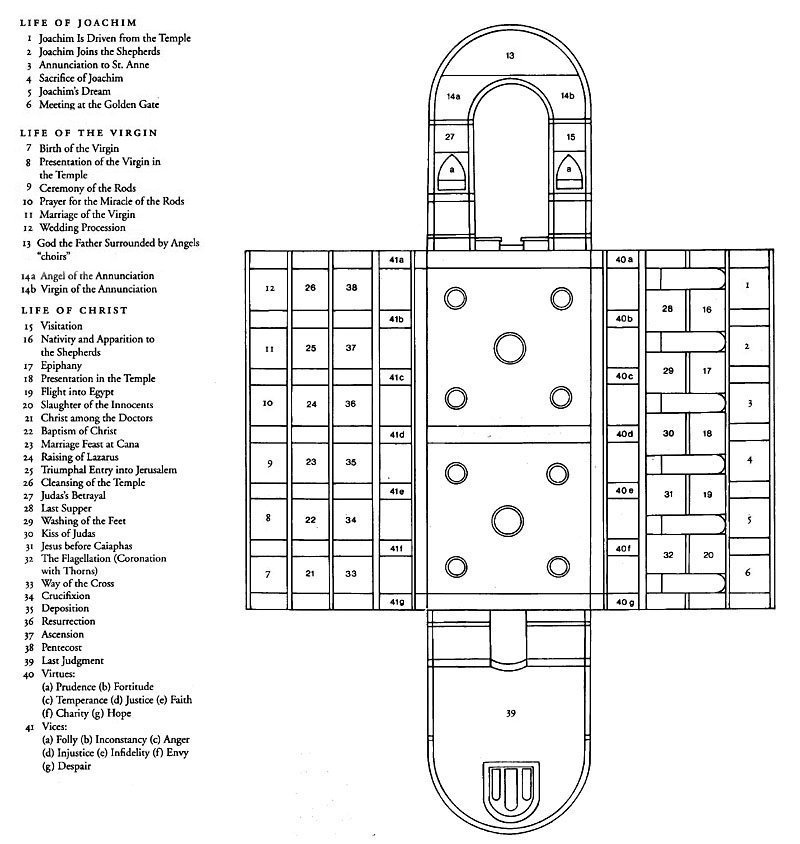

When studying the layout of the various panels, you come to realize the artist created a very complex structure: vertically the panels foreshadow each other; horizontally, the panels move across time. Below is a map, showing the various scenes in each of the panels.

Faith and Light in Scrovegni Chapel

My favorite work is the Final Judgement on the chapel’s west wall. Christ in Majesty overlooks those condemned to hell and those whose good deeds permit entrance into heaven. The complexity of the work astounds, and the level of detail that Giotto brings to the final days provides further evidence of his incredible talent. Many scholars credit the artist for creating the first shift toward the Renaissance. Another significant shift wouldn’t come until 1430, when Masaccio and Masolino frescoed the Brancacci Chapel of Florence’s Santa Maria del Carmine church. Then, our human form would begin to take on its full and complete representation.

This work holds more mysteries than you can imagine. When Giotto studied the way light entered the chapel, he came to understand that at certain times of the day, certain months of the year, bright sunlight bathed the west wall of the chapel.

As Giotto further considered the design for the Judgement fresco, he must have given a great deal of thought to the impact light and lenses could bring to his work. As you study the halo of Christ, you will notice three circular disks, or lense within the raised golden shape. Research conducted by numerous art experts has revealed that when sunlight illuminates the west wall, the three disks reflect the rays of the sun into the chapel, creating a near miraculous vision of both the power of faith and its physical manifestation — a stunning sight to see.

Illumination

One final intriguing skill demonstrated by Giotto concerns the figures of the devils and angels in The Last Judgement. Giotto painted those figures using white paint with barium. This paint absorbs light during the day and creates a glow in the dark effect at night. The fresco of The Last Judgment glows with unearthly illumination at night, “the time of the devils” as Giotto described it.

Giotto’s Humanist Approach

Another of my favorite panels is The Betrayal of Christ. As you study the faces and the physicality of the fresco, you can begin to see what Giotto accomplished. The faces of soldiers and disciples alike clearly portray anguish, fear, disbelief, and anger — all human means of expression — that give us a sense of the portrayal of humanity to come later in the Renaissance.

I have visited the Scrovegni numerous times, and it never fails to take my breath away. To think that a man and his collaborators created this matrix of breathtaking beauty over seven-hundred years ago astounds those fortunate enough to view them.