Ah, Caravaggio.

Some have called him “Baroque’s Bad Boy”, but regardless of the nickname anyone gives this extraordinary painter, those words will forever fall flat when in the presence of his work. You will find numerous works by Caravaggio in Rome, but when you walk through a museum anywhere in the world, you can instantly recognize his work. The strokes of his brush, the use of light, draw us like moths to flame. From such enormous talent, created on a foundation of death and tragedy, came one of the most revered of the Mannerist painters.

He was born near Milan. In the mid-16th Century, the plague stole nearly all of his family from him, and the shadow of death — of those losses — deeply influenced his life and work. After apprenticing with a (not proven) student of Titian, Simone Peterzano, he went on to work in Rome, Naples, Sicily and Malta.

When you study a Caravaggio, pay attention to the dark backgrounds. The figures stand forward, illuminated or shadowed in the foreground; the dark depths of the unknown, perhaps the curtain of death, always hovers nearby.

Dott.ssa Roberta Lapucci, a renowned expert on the works of Caravaggio, brought to light a theory that the artist used the Camera Obscura in many of his paintings, a subject for another article sometime in the future.

I have provided, here, the “Trail of Caravaggio in Rome.” The list is not in any particular order, that is by date of painting, location of the works in Rome geographically, or the subject matter.

Our guests have chosen any number of ways to view these masterpieces; ultimately, I believe it doesn’t matter in what order you view them but view them you must.

Caravaggio’s genius is unmistakable.

Contarelli Chapel, San Luigi dei Francesci, Rome:

The Inspiration of Saint Matthew

This is, unreservedly, one of the favorites. The startled gaze of the saint, the folds of illuminated fabric and the gentle way the angel enumerates what Matthew must write are so unique and purely indicative of Caravaggio’s genius.

The Calling of Saint Matthew

Many art critics and art historians consider this Caravaggio’s capolavoro, his masterpiece. Note the light on the legs under the table, the facial features illuminated over Christ’s shoulder, and the finger pointing to the man. Wait. Who is Christ pointing to? If you follow the direction of Christ’s pointing finger, it appears the older man with glasses is Matthew. Look again. Perhaps Matthew is the bearded figure pointing away from himself as if to say, “What me? No. You mean him?” Study Caravaggio. The mysteries deepen.

The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew

When you study the figures in the back of the painting, you will see a man with a beard — none other than, experts believe, Caravaggio. The deft use of light, again, leaps from this work. Details bring you into this canvas, deepening your encounter with Michelangelo Merisi: the wings of the angel whose lower leg is visible behind the reaching palm frond, the shadowed definition of muscle on the executioner, and the light on the fingers of a follower.

Doria Pamphilj Gallery, Rome:

Rest on the Flight into Egypt

This painting is a quandary. It is so different from the other works by Caravaggio that I would not be surprised if, someday, they determine that it isn’t his work. The gentleness of the sleeping Madonna, the soft texture of skin on the angel, and the Madonna and child are so ‘out of step’ with the masculine aggressive strokes we see in other Caravaggio’s work. The hypnotic gaze of Joseph, who at this juncture must be more than fatigued, communicates awe, reverence and not a small degree of confusion.

Penitent Mary Magdalene

As with the Rest on the Flight into Egypt, this gentle portrait of a lovely young woman, perhaps the same model who inspired Caravaggio on the Egypt painting, elicits calm, repose, a quiet moment. The master’s touch is certainly here; note the reflection of light at the base of the jar sitting on the floor next to his dozing figure.

Capitoline Museum, Rome:

The Fortune Teller (First Version: 1594)

Caravaggio created two versions of this work. This one, dated 1594, is the earlier of the two. The later work, 1595, resides in Paris’ Louvre. The young man, who is clearly besotted with the gypsy, does not take notice that she has removed a ring from his finger. I can never find any sign in the quality of the work that indicates Caravaggio worked as quickly as he did; note the fine feathers on the man’s hat, the delicate embroidery on the blouse, and the subtle brocade of the man’s tunic. Incredible.

Pinacoteca, Vaticana, Rome:

The Entombment of Christ

A painting whose composition points us to death, to the earth, to stone. From the outreached arms of Mary of Clopas (left), the bowed head of Mary Magdalene is nearly lost in the shadow that contrasts with the habit worn by Mary the mother of Christ. Her outstretched hand parallels the slab of the tomb’s stone. The structure of the group is triangular, upper right to lower left. Christ’s right hand touches the stone, the fingers extended, pointing to the earth.

Galleria Borghese, Rome:

Madonna and Child with St. Anne

The serpent of heresy is imprisoned under the feet of the Madonna and Christ child. This work was not well received by those in the Vatican and, after a brief exhibit, was purchased by Cardinal Scipione Borghese, an avid patron of Caravaggio.

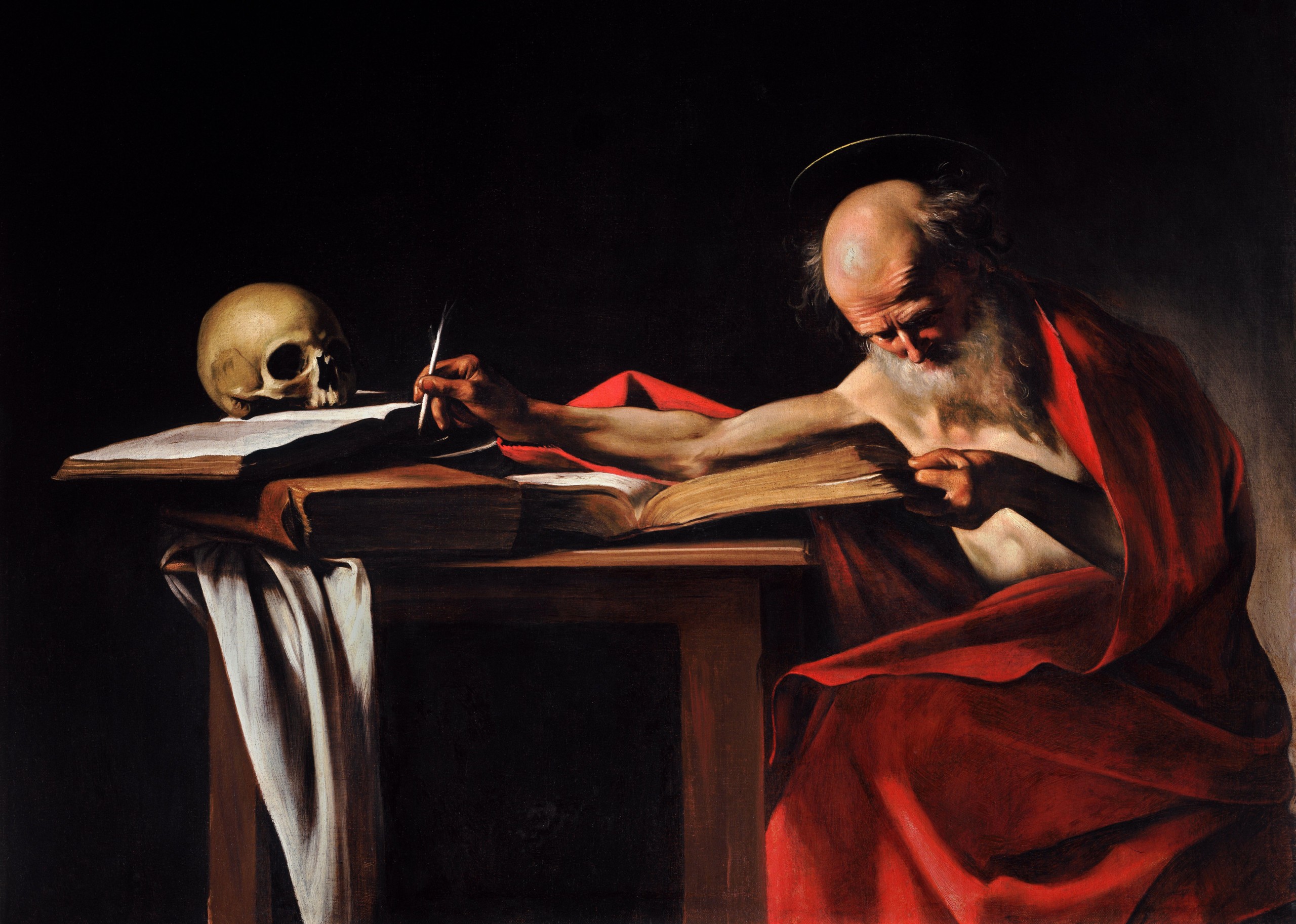

St. Jerome Writing

The reflection of warm light against the skull parallels the light glowing on St. Jerome’s bald head. These two indications of light connect the viewer to the message: life is fleeting; death awaits. This venerated Saint creates a bridge between the two as a writer, a scripter, who records and passes on to future generations what matters.

Boy with Basket of Fruit

Mario Minniti, a friend from Milan, posed for this work. He may also have posed as the young man taken in by the gypsy in The Fortune Teller (First Version) referenced above. Regardless, what draws most views to this work is the basket and the contained fruit: the refection of light on the apple, the warmth of the peach, the grapes so ‘real’ you could almost reach up and pick one. Such mastery took a great deal of time and, given the year that this was painted, Caravaggio may well have been not just refining his craft; he was also demonstrating his early mastery.

Young Sick Bacchus

This painting elicits the same reaction from most viewers: they feel sick. It is a self-portrait of the young painter after what many medical experts believe was the onset of Malaria. The work was done using a mirror. In a future article, I will present information about the Camera Obscura and how Caravaggio used it in his work.

David with the Head of Goliath

I have always believed that what we see in this self portrait of the artist, the head of Goliath, depicts Caravaggio’s psyche. At this stage of his career, he was exceptionally well known, yet was troubled and known for fits of anger and rage. Some conjecture this David is not modeled from the artist’s studio assistant, Cecco di Caravaggio. Rather some believe this painting represents a double self portrait of a younger Caravaggio wistfully holding the head of his older self, full of regret, tinged with revulsion and sadness.

Cerasi Chapel, Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome:

Crucifixion of St. Peter

Early writings about this piece are unkind. The butt of the man protruding out into the forefront of the painting offended many, as this painting portrays the death of that same Peter for whom St. Peter’s is dedicated. The dirty feel of the man holding the cross and the complexity of raising the cross, as Caravaggio designed it, all tend to confuse the viewer. For those reasons alone, it makes you stop and wonder at the sheer physicality of it all.

Conversion on the Way to Damascus

What a depiction of a man in religious ecstasy this is. Laying on the ground, Paul is suffused in light, arms outstretched to some source of his conversion. Viewers are drawn in, wondering what he sees. The man holding the reins quietly comforts the horse. I smile at the genius of the way the artist raised the horses’ leg so that the illumination of the leg provides even more of a frame to the center of action.

Church of Sant’Agostino, Rome:

Madonna di Loreto

This work, as well, offended many in the church. The dirty feet of the Madonna, the clothing and feet of those who come to adore the child, all chided church leaders who resisted an image of the Madonna who wasn’t pure, and clean, and who stood surrounded by the filthy poor. I interpret his painting as a snub at the Church leaders for their excesses.

Villa Ludovisi, Rome:

Jupiter, Neptune and Pluto

A special note: Caravaggio painted this work on canvas, not fresco, though it is a ceiling painting in the villa. Tieoplo, Allori, and others were known experts for foreshortening in ceiling work. Here, Caravaggio demonstrates a skill only once used, that we know of, using that same technique. It is as if you are truly looking up at living things: a naked Neptune, Jupiter accompanied by an eagle —a winged God holding his planet, and Pluto holding Cerebus, the three headed dog.

Palazzo Corsini Collection, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Rome:

NOTE: The Palazzo Corsini and the Palazzo Barberini are two locations managed by the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica in Rome.

St. John the Baptist

One of a number of St. John’s painted by Caravaggio, this one is the most calm, the most at ease. Wrapped in the signature iconography of his age in portraying the young saint — red cloth — the shadows on the cloth and the illumination of the youthful man before he baptized the Christ, all come through in the work.

St. Francis in Prayer

Before the swirl of a rock wall, St. Francis contemplates his life and death. There is a story about Caravaggio and his apartment in Rome: he drilled a hole in the ceiling of his apartment so light could enter his studio. This caused no end of issues when the time came to leave the city. It is interesting to note that a circle of light rests on the right shoulder of the saint, a sure sign that this was painted in that same studio.

Palazzo Barberini, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Rome:

Narcissus

This is my favorite of all the Caravaggio paintings. It is so appropriate in today’s world; we focus on selfies and ‘us’ rather than those out in the world with whom we miss actual connection. Don’t look at your reflection too long, your social media account might lapse.

Judith Beheading Holofernes

This work is right up there with Artemisia Gentileschi’s painting of the same moment. It is a stupendous judgement against the way women have been subjugated across the centuries, a Bible-true story that gives back to that male dominated world a violent, bloody, and well-deserved retaliation for all those years of abuse. It sparkles with tension, disgust, darkness – and I love the maidservant holding the leather satchel. Guess what goes in it?

**************

I hope this overview of Caravaggio’s work in Rome will entice you, once we can travel again, to get to Rome for a long visit. Other masterpieces of this artist reside in Naples and Malta, as well.

Enjoy and thank you for following our blog posts!